Why does everyone want an e-wallet license?

Cred has one. Jupiter has one. And even Adani recently got one. So, what makes the e-wallet license lucrative for all these fintechs? And why do they covet it?

At some point in 2016, Paytm’s e-wallet was the most popular fintech product. Until UPI was launched. Obituaries started flowing in for the humble e-wallet. One of which announced the demise of e-wallets with a sense of inevitability:

In October 2016, two months after UPI was launched, the ratio of wallet-to-UPI transactions stood at 96:4. By March 2017, the scales had tipped massively. Wallets were left with a far smaller 36% of the share as UPI raced ahead to claim 64%, data from Bengaluru-based payments platform Razorpay show.

“We noticed that UPI is being used for the same things that wallets are used for—high-frequency, low-value transactions,” Harshil Mathur, Razorpay co-founder and CEO, told Quartz. Only the UPI platform’s transactions cut out the cumbersome intermediary step of loading money onto a platform before making a payment, which wallets still require. Bank account holders in India always exceeded in number than e-wallet users—all of whom can start doing e-commerce transactions directly with UPI.

The Indian government’s payments gateway is a mobile wallet-killer, Quartz

E-wallet’s almost immediate surrender to UPI was not surprising. UPI was a superior payment product and Indians loved it. Importantly, it impressed both the customers and merchants (unlike all other payment options before it). Since both e-wallets and UPI competed for small ticket payments, one would eat the other’s lunch. From that point, e-wallets have consistently seen lower transaction volumes than UPI. In FY 2023-24, for example, UPI saw 16 times the volume of transactions on e-wallets.

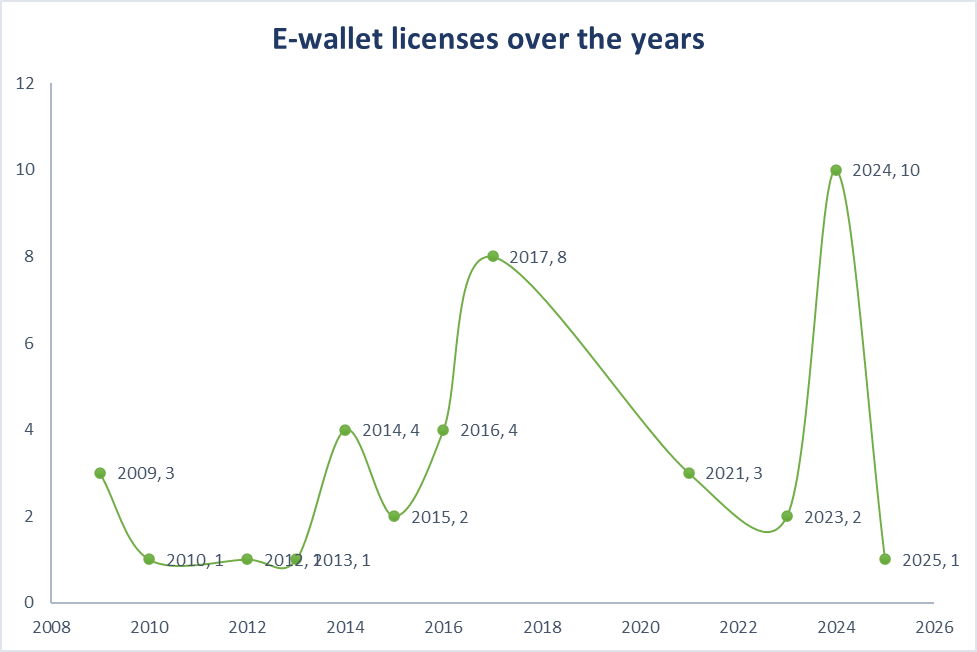

Naturally then, this meant that fintechs weren’t too keen on getting on the e-wallet bandwagon anymore. In the 6 years between 2018 and 2023, only 5 new firms got an e-wallet license (as opposed to 8 just in 2017). In the same time period, 15 players got approved to launch UPI apps.

Okay, you know where I’m heading with this. E-wallets were down and out. Probably even buried. So, just how did they do an Undertaker and return from the dead?

2024 saw the highest number of e-wallet licenses1 being issued in a year ever. What’s more interesting is the diversity of applicants who got these licenses - fintechs across the spectrum. For example, Jupiter has a neobank offering at the heart of things. While Cred primarily does credit card payments. So, what gives?

I have a theory. Which is that if you sit down and have a heart to heart chat with a fintech founder in India, they’d tell you that they want to be a bank; but, they hate the complexity that comes with it. There are multiple reasons for this.

If you, a new-age fintech in India with a 2 syllable name, a beautifully designed app and dreams of changing banking in India go to the RBI and ask for a banking license – chances are, the bouncer at the door will turn you away (cue: the eligibility criteria). If you do get past the bouncer, maybe the RBI will maybe pat you on the back for having good ideas but will quickly say no. The decision makers at the RBI are miserly with banking licenses. Since 2016, the rejection rates for banking license applications are between 80% (for universal banking licenses) to 88% (for small finance bank licenses).

Sure, you can’t get a banking license. You rue it. But maybe you’re better off without it, with all that compliance headache. You’re determined. So, you do the next best thing – join hands with an existing bank for a neobank offering.2 The terms of engagement are clear: You’ll design your app, the bank will do the banking (handle funds). Your partnership has regulatory blessing, even if impliedly. What about customers? All existing banking apps were made in the Paleolithic Age. If they did want to use stone tools, they’d use it to express frustration at the state of things, you think. Eventually, you hope for them to love your app and avail your other services (say, lending). Except, most of that doesn’t pan out the way you think it will. To begin with, the idea doesn’t interest a lot of banks. Some large banks see you as a competitor, while others think it is a hassle. But you do eventually find banks who vibe with you.

As soon as you begin, you realise some harsh truths. One of which is that irrespective of what the press releases say, this is not a partnership of equals. You realise you can’t change the customer experience much with just the app. Maybe you want a seamless KYC to streamline customer onboarding and cut customer acquisition cost. The bank says NO. That’s a banking function and they call the shots on that. You keep pushing to do more of the ‘banking’ to fix the customer experience, but they don’t budge. “Regulatory risks”, they tell you. Maybe they’re right. Because the regulator seems unhappy with their child’s love marriage. They ask the banks not to share card transaction data with you. And in one case, they stop a partner bank from allowing international transactions. You now worry if the rug might be pulled from under you one day.

By now, you’re probably asking - okay but, what has that got to do with the resurgence of e-wallet licenses? The answer is that the e-wallet has in many ways become pretty similar to a bank account. As such, an e-wallet license becomes ideal for any fintech which aspires to offer a payment account like offering and wants to avoid the constraints that come with banking partnerships.

An e-wallet holder today can do the same things that a traditional retail bank account holder does - park funds, make offline payments, pay bills and most importantly - pay through UPI to merchants and friends. E-wallets don’t compete with UPI anymore. Regulatory intervention has ensured that you can pay through your e-wallets using UPI (just like bank accounts). Now, I’m not arguing that an e-wallet can perfectly substitute a retail bank account for everyone. It is still not as feature rich as a bank account. For example, e-wallets don’t pay any interest on deposits (unlike bank accounts). However, recent trends suggest that bank accounts are themselves increasingly being seen as payment wallets instead of traditional ‘savings’ instruments. Customers looking for returns are turning to mutual funds or gold, as opposed to bank accounts. Likewise, e-wallets also come with an INR 2,00,000 (roughly USD 2,300) monetary cap on the amounts they can hold. Again, that’s not that big of a deal for most people as the average ticket sizes for retail payments remain small.3

Cool, but what do fintechs get out of an e-wallet license? Two or three things. One, they become the masters of their destiny. They get control over the entire customer journey. Being able to control both the banking and the app are critical to building a good customer experience. It also helps that they can now build the entire customer journey as per their risk appetite, all without the complexity of managing a delicate banking partnership. The obvious but incredibly beneficial tradeoff is that they can almost guarantee avoiding a rug pull, at the cost of taking responsibility for regulatory compliance. Two, reduced costs and some revenue. Strategically, fintechs may choose to open a small KYC e-wallet (which can hold up to INR 10,000) at first. Since small KYC wallets can be opened with just the mobile number verification, this can significantly reduce the upfront onboarding cost. Slowly, these customers can be nudged into signing up for a full KYC. Given that UPI on bank accounts is free (by regulation), there’s little opportunity to make revenue from payments with bank accounts. But with an e-wallet, it is regulatorily permissible to charge commissions (technically, MDR4) on UPI payments to large merchants (for ticket sizes >INR 2000). Interchange5 on card payments (1-2%) is available with both co-branded bank accounts and e-wallets. Except that, fintechs with their own e-wallet licenses won’t have to share it with their partner banks. Three, it is untested how valuable data from usage of e-wallets can prove for cross-selling avenues like lending. But it can certainly supercharge fintechs with better insights into the behaviour of their users, without the regulatory sword hanging over their necks.

Make no mistake, an e-wallet license is not the panacea for all ills. A co-branded banking partnership certainly offers more avenues of revenue (think commissions for driving CASA deposits, new accounts, and fixed deposits).6 And maybe even better insights into creditworthiness of their customers (if they open salary accounts). But for most fintechs (and their users), an e-wallet today seems good enough!

When I use the term “e-wallet license”, I technically mean an authorisation from the RBI to issue prepaid payment instruments or PPI. And again, I’ve used e-wallets to colloquially refer to all form factors of the PPI – cards and wallets.

I’m focusing on retail neobank partnerships here.

Average transaction size in H1, 2024 for UPI was INR 1478 and for debit cards INR 2830 - India Digital Payments Report.

MDR is a fee that an issuing bank charges a merchant for accepting payments from their customers via payment instruments like cards.

Interchange fees is a transaction fee charged between banks for processing card payments. When a customer makes a purchase using a card, the merchant's acquiring bank pays the interchange fee to the customer's issuing bank.

Very interesting read, Priyam!